Port Jervis, New York, history

History

Part I - Prehistory to the end of the Civil War

The history of what is today’s Port Jervis and its region is a rich and ancient one. Like many places, it has seen both good and bad, tragedy and triumph, booms and busts, predictable day-to-day life and rapid change. From the time when the only humans who lived here for thousands of years were indigenous peoples and the pre-Revolutionary War years of early colonialism to present, in some ways it has been and continues to be a microcosm of America. What follows is a work in progress two part overview that includes some of the more prominent historical aspects of Port Jervis and its region.

Found here are over 400 million year-old marine fossils and evidence of human occupation going back some 12,000 years. Those first peoples who remained when the largely French Huguenot colonists initially arrived near the start of the 18th century were the Minsi, a sub-group of the Lenape (Delaware Indians) who spoke the Munsee dialect and to whom the fertile Neversink River bottomland running through today’s Port Jervis was known as “Magagkamack,” a phrase that has been interpreted as “pumpkin field” or “red lands.” It was in the vicinity of Port Jervis that Minsi Lenape made their traditional councils while the larger region in which Port Jervis is located was “Minisink,” a word still used today as a geographic identifier and place name.

Named after William of Orange, a Dutch prince who in 1689 became king of England, Port Jervis is located in Orange County, one of New York’s original counties established in 1693.

Prior to the War of Independence, what became the Port Jervis area saw border claim disputes called the New Jersey Line War as well as hostilities related to the French and Indian War that produced the once revered but now generally reviled local folk hero, Tom Quick, whose truth embellished history tells that to avenge the death of his father, he made killing Native people his life’s work.

The Port Jervis area, which was then a sparsely populated frontier outpost, also bore witness to Revolutionary War hostilities that included two Loyalist raids headed by the famed British educated, Mohawk military leader and diplomat, Joseph Brant (Tyendinaga). The second attack resulted in the brutal 1779 defeat of Colonial forces at the Battle of Minisink Ford, about 30 miles up the Delaware River from Port Jervis. A stone house known as Fort Decker that was burned during the 1779 raid survived to be rebuilt in 1793 and become listed on the National Registry of Historic Places. Today, Fort Decker serves as a museum in Port Jervis owned by the Minisink Valley Historical Society.

Following the Revolutionary War the need to be self-reliant and relative isolation of what became today’s Port Jervis area continued but moved into a new phase when in 1825 word arrived that the route of one of America’s first million dollar private ventures, the Delaware and Hudson Canal, was planning to pass through the hamlet. The importance of this progression can be measured by the canal’s chief engineer, John B. Jervis, being chosen then to serve as the community’s namesake.

Because the transportation of coal from northeast Pennsylvania mines to the Hudson River was the main reason why the D & H Canal was built, researching and ordering the first steam engine locomotive to run on commercial railroad tracks in the United States is another in the list of lifelong accomplishments credited to the prominent 19th century American civil engineer after whom today’s city of Port Jervis is named.

With the canal’s arrival and 1828 opening would gradually come growth and commerce that just one generation later received another major boost when the first Erie Railroad steam engine made its way to Port Jervis in 1848. This further step into an era of expansion ushered a boom that in 1853, as the railroad make its importance clear, found Port Jervis elevating itself to formally become a village. Gone were the days when crops were grown in the Delaware River flats that were now taken over by loud and bustling railyards with their landscape changing tracks, buildings and structures. Port Jervis was fully part of the industrialized age of progress and steam. Today’s downtown Port Jervis business area is a reminder of what grew up there from the railroad’s early hive of activity.

Answering the call during the Civil War, the hundreds of men from the Port Jervis area who served included those with the 124th New York State Volunteer Infantry “Orange Blossoms” who saw fierce combat at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg before being among forces gathered around the war’s end near the 1865 surrender of the Confederacy at Appomattox, Virginia.

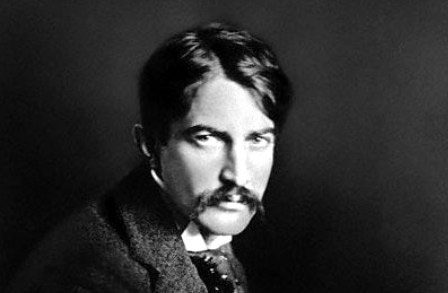

While there is no hard proof, there are very good circumstantial reasons to believe the influence Port Jervis veterans had on noted 1890s American author, Stephen Crane (1871-1900), who had lived in Port Jervis in his youth and returned here for much of his short 28 year life, was strongly reflected in his most famous work, The Red Badge of Courage, as well as among his earliest to last.

As the Civil War neared its 1865 close the directors of the D & H Canal Company wisely expanded its enterprise to develop the Delaware and Hudson Railway whose versions of operations and ownership of track rights continued into the last decade of the 20th century – well over 150 years from the company’s early canal days.

The next era, known as “The Gilded Age,” is one whose name is taken from the title of the only book Mark Twain co-authored – The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. (1873)

Stephen Crane

“My idea is to come finally to live at Port Jervis or Hartwood. I am a wanderer now and I must see enough but – afterwards – I think of P.J. and Hartwood.”

Stephen Crane's October 29, 1897 letter from London, England, to his brother William in Port Jervis, New York.

Like his people before him Stephen Crane had an adventerous spirit. The first of his family arrived in what would become the United States more than a century before the signing of the yet to be born nation’s Declaration of Independence. That footfall took place when his namesake ancestor was among a small group of individuals known as the Elizabethtown Associates who established the first permanent English settlement in New Jersey after the Dutch surrendered that and other territory in 1664. His Revolutionary War namesake, who reportedly died of wounds received from enemy bayonnets, was an accomplished figure in Colonial era New Jersey including having been a state delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774. While one of Crane’s most distinct traits was wanderlust, Port Jervis and its region were almost certainly the place he most regarded as his true home and not without good reason.

By the time his father’s work in the Methodist Church brought the six-and-a-half-year-old to Port Jervis in April 1878, Stephen, the last of fourteen children, had already lived in two other communities. His days in the Drew Methodist Church parsonage on East Broome Street lasted less than two years when the sudden February 1880 death of his preacher father, the Rev. Dr. Johnathan T. Crane, required him, his brother Luther and mother to find other lodging. As his mother, the ardent prohibitionist, Mary Helen Crane, retreated with Luther to the Methodist stronghold of Asbury Park, New Jersey, to consider her next actions, Stephen spent several months living in nearby Sussex County, New Jersey, with the brother who became his favorite over five others – Edmund B. Crane. In the summer of 1880 Stephen, his mother and Luther reunited in Port Jervis to live in a house his recent law school graduate brother, William H. Crane, had taken at 21 Brooklyn Street and where, for a time, his scholarly sister, Agnes, joined them. This remained Stephen’s home until his mother brought him with her when she returned to Asbury Park three years later. These essentially five consecutive years Crane lived in Port Jervis could arguably be said to have been the longest span of time he ever continuously called one place home.

Following this first period in Port Jervis Stephen attended public and private schools in New Jersey and New York State where at the Hudson River Institute at Claverack, located about 40 miles south of Albany, he rose to the rank of captain in the school’s cadet corps. Next in line were short, disinterested attempts at two colleges, first at Layfayette in Easton, Pennsylvania, and then at Syracuse University in central New York, an institution that Crane’s great uncle, Rev. Jesse Peck, played a large part in founding. It was here that in 1891 he met fellow Syracuse University student, Port Jervis native, Frederic M. Lawrence, whose new found friendship would help lead the future author back to the community where much of his boyhood and early adolescence were spent. Beginning that summer through his 1897 departure to Europe Crane continued to visit Port Jervis and nearby areas including to camp in Pike County, Pennsylvania. He likewise greatly enjoyed spending time in Hartwood, Sullivan County, New York, where in 1895 Edmund had found his home on part of the large land holdings their brother William obtained for speculation and use as an exclusive game and outdoorsman preserve which still continues to this day as “The Hartwood Club.”

From some of the first pieces of fiction he ever had published, which are collectively known as Sullivan County Tales and Sketches (1892), to his masterwork, The Red Badge of Courage (1895), and his last published writings called Whilomville Stories (1899-1900), that are loosely based on his childhood growing up in Port Jervis, the influence the Port Jervis area had on Crane and his work can hardly be overstated. It is to be similarly noted that the given name of his next door childhood neighbor on Brooklyn Street, Maggie Belle Ogg, is also that of the title character of his first major work: Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. (1893)

Crane’s years-long familiarity with and easy access to Civil War veterans who lived in Port Jervis almost certainly played a significant part in his inspiration for The Red Badge of Courage. Not only did his brother William have his law office in the same important Farnum Building (1882) where the Port Jervis chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic veterans’ organization had their post, but several of his Brooklyn Street neighbors were veterans. One of those former soldiers, Philip M. Ogg, was Maggie’s father.

Philip and his brother, John, both served in the same Company F of the 124th New York State Volunteer “Orange Blossoms” infantry unit that had enlisted in Port Jervis. But where Philip survived the war his brother John did not. After being left behind on the battlefield, taken prisoner, and released for care back to Northern forces, he died of wounds suffered at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, the fight that Crane revealed in his short story, “The Veteran” (1896), to be that told of in his best known work.

Although its outcome is not like the tragic real life experience of the Ogg brothers, another war story Crane wrote in 1896 called “The Little Regiment” is about two brothers who face combat together and one of whom is feared lost.

A local folklore tradition that took root in the 1980s believes that Crane interviewed veterans in the then village’s Orange Square park still found on Pike Street. However, even though there are strong circumstantial reasons to believe Crane spoke with veterans, there were far more likely places for that to have happened than Orange Square and, in any event, there is no actual proof that he ever did so in Port Jervis or at any of the many other places he lived before writing his famous war novel during a time in New York City and his brother Edmund’s in Lakeview, New Jersey.

While Stephen and much of his family lie buried in Hillside New Jersey’s Evergreen Cemetery near his November 1, 1871 birthplace in Newark, his brother Edmund, who later in life became the Port Jervis director of streets, found his final resting place in Port Jervis at Laurel Grove where his wife, Mary Louise, and their own son, also named Stephen, join him.

Stephen Crane died on June 5, 1900 near Germany’s Black Forest where he had sought medical treatment for the tuberculosis that took his life. Over the course of his 28 years the short-lived writer was a newspaper man, poet, war correspondent, novelist, and creator of many works of fiction whose gifts made him one of the most famous American authors of the 1890s and earned him friends such as H.G. Wells and Joseph Conrad. Although his free-spirited lifestyle during a time when social conformity and measured constraint were the norm made him a controversial figure during his own era, today he is recognized as a great American author and a famous, local historic personality Port Jervis and its region hold in high regard.

Did you know that...?

- D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, and other silent movie notables pioneered the film industry in the Port Jervis area.

- A highly detailed 1958 study by the National Research Council analyzed the effects a 1955 Hurricane Diane flood rumor had on Port Jervis.

- Three United States Representatives of Congress are buried in Port Jervis.

- Major League Baseball Hall of Fame inductee, Bucky Harris, was born in Port Jervis.

- E. Arthur Gray was Port Jervis’s longest-serving mayor, completing 5 1/2 terms from 1978 to 1988 and then later becoming a New York State Senator.

- 1934 day and night photos of electric lights installed in Port Jervis are featured on the Smithsonian Institution web site.

- Fort Decker is a stone house reconstructed in 1793 from remains of an earlier, c. 1760 building that was burned during a 1779 raid by Britist loyalists and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- The Library of Congress web site includes a highly detailed, magnifying 1920 aero map of Port Jervis.

- Port Jervis resident, John Newton Howitt, painted pictures for advertisements, covers for pulp novels and leading magazines as well as a WWII poster.

- Stephen Crane, renowned author of the “Red Badge of Courage,” lived and wrote in Port Jervis.

- Former Port Jervis High School wrestlers, Ed and Lou Banach won Gold Medals in the 1984 Olympics. (Ed was light heavyweight and Lou was heavyweight).

- An Urban Legend about alligators living in the New York City sewers has a connection to Port Jervis as documented by a July 3, 1929 reference in the New York Times.

- The “Kalin Twins“, a singing duo made famous by their 1958 pop song, “When,” were raised in Port Jervis.